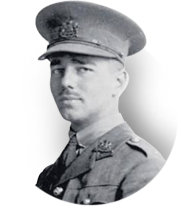

Owen’s life and death

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen was born in Oswestry on the 18 March 1893. He was educated at Birkenhead and later Shrewsbury and took the University of London matriculation exam in September 1911, but did not gain a place. Following a period as a lay assistant at Dunsden, near Reading, he journeyed to Bordeaux to teach English at the Berlitz School. Owen remained in France at the outbreak of the First World War but returned to England in May 1915. In October he joined the Territorial Forces of the 28th London Regiment (the Artists’ Rifles). His interest in writing poetry developed during periods of military training, which included such basic duties as as horse riding and trench digging.

In January 1917 Owen joined the Second Manchester Regiment as a second lieutenant and witnessed the horrific action that took place in the Somme. He likened the Western Front to a: ‘pock-marked like a body of foulest disease, and its odour is the breath of cancer. I have not seen any dead. I have done worse. In the dank air I have perceived it, and in the darkness, felt. … No Man’s Land under snow is like the face of the moon, chaotic, crater-ridden, uninhabitable, awful, the abode of madness’.

Owen suffered concussion at Le Quesnoy-en-Santerre but he engaged in further action at Selency, an experience which led to his suffering from the condition known at that time as neurasthenia, or chronic fatigue and memory loss. The stress on Owen’s nerves led to a diagnosis for specialist mental health treatment and on the 26 June 1917 he entered Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh. As part of his recuperation he edited the hospital magazine The Hydra, studied German language and literature and resumed composition of poetry. Owen was encouraged in his writing by the psychologist Dr Arthur Brock, but interest in his case was also shown by the anthropologist WHR Rivers who specialized in treating the neuroses brought on by the battle trauma. Owen was also greatly inspired by the opinions of another of Rivers’s patients, the poet Siegfried Sassoon. Sassoon, who had earned a reputation as a dissident for questioning the government’s role in supposedly prolonging the war, was the author of the recently published The Old Huntsman and Other Poems, which Owen read and admired. In fact it was while he sought Sassoon’s autograph on the book that they first made one another’s acquaintance.

The impact of this meeting can be gauged by a letter that Owen wrote to his mother on New Year’s Eve 1917: ‘I go out of this year a poet … as which I did enter it. I am started. The tugs have left me; I feel the great swelling of the open sea taking my galleon’. Owen published only a small number of poems during his short life. One of them, Futility, a verse Britten set in War Requiem, appeared in The Nation in June 1918. It speaks of the powerlessness of the natural world to heal the wounds imposed by war. Its tone of quiet desperation and use of simple imagery heightens the sense of waste of human life. Owen returned to active service in France, taking his place in the 5th Manchesters at the forefront of battle where he thought that his condemnation of war would be all the more pronounced. ‘I am glad’ he said ‘That is I am much gladder to be going out again than afraid. I shall be better able to cry my outcry, playing my part…’ In October he was awarded the Military Cross for outstanding gallantry at Amiens and later that month joined the campaign at the Sambre-Oise canal. Owen was killed during an attack on the 4 November 1918, one week before the declaration of the Armistice—the day on which his family learnt of his death.

All quotations taken from The Poems of Wilfred Owen, edited with a memoir and notes by Edmund Blunden. London: Chatto & Windus, 1955. This is the edition from which Britten worked whilst writing War Requiem.

© Britten-Pears Foundation

© Britten-Pears Foundation © Britten-Pears Foundation

© Britten-Pears Foundation